‘I have often wondered if a conference based upon grief might be instrumental in motivating people to care abut the Earth. If we were to grieve for what is being lost, then we might come to value what we have.’

Alyson Hallet, Geographical Intimacy, Amazon 2016

In June 2016 I attended an all-night gathering called We Weave and Heft by the River. It took place in a small woodland on the Sharpham estate in South Devon, and was led by the three members of the Coastal Reading Group: Bibi Calderaro, Margeretha Haughwout and Christos Galanis. I joined them for the first leg of their session, from 10pm to 1pm.

The gathering was billed as an ‘all-night grief workshop’, one that would invite a turn towards the growing sense of loss that gathers around our culture’s impact on non-human life. The idea both appealed me, and provoked a vague sense of alarm. What exactly would it entail, to enter that territory with a group of strangers? And ecocide was not, in fact, the theme that had brought us together. The Coastal Reading Group’s workshop was embedded within the Schumacher College’s two-day forum on the theme of Landscape, Language and the Sublime. But if it wasn’t centre stage, ecocide was most definitely present, nonetheless. It’s looming, background presence shadowed, explicitly or implicitly, all of the conversations that I encountered during those two days. Like a distant noise-off that lent a familiar sense of dislocation, surreality even, to the diverse and vibrant exchanges taking place. Pretty much all of the talks and events at this forum fell under the broad umbrella of ‘eco-criticism’, an idea that - at times, anyway - seems to bring with it the strange proposition that the accelerating collapse of the biosphere provides, first and foremost, a useful occasion for some serious and innovative thinking.

During the three hours I spent under a rain-pattered awning in the dark of the Sharpham woods, the discussion took an altogether less heady turn. It was, in the main, about sharing memories, and telling stories. More than that, the manner of the sharing was, in itself, about the power of ritual, about the weight of physical gestures, and of tactile, living materials, to ground and embody grief. The power of ritual, to allow us to set down the specific griefs, spoken or unspoken, that we carry around with us. To hand them over.

As each new story emerged into the unhurried space of that ritual, an elected witness was asked to take a length of twine, to thread it through a clay seed-ball that the organisers had prepared, and then to bind the teller’s story round and around that ball of packed earth, as they listened. At the end of the night, these wool-wrapped seed-balls were to be buried, with all of the night’s memories bound into them, and left to seed cornflowers, poppies and other flowers in the Sharpham soil.

The memories that surfaced one by one during that first phase of the night included personal bereavement. The recent loss of fathers was a common theme. They included the lasting shock of both witnessing, and being an inadvertent party to, a wild animal’s suffering and death. They included seemingly incidental memories, from childhood or from the margins of busy lives, that stood out as intimations of those greater currents of loss that our individual lives are caught up in, but which remain somehow too big to see.

As I listened to others tell their stories, I was struck by an image from my own childhood, returning across more than 40 years. How each summer in Oxfordshire, the car windscreen would have fly splats covering it after every journey. How, the morning after a night drive, the grille between the headlights would be plastered with the bodies of moths drawn to the headlamps. And with that last, another image: the thick swirl of whitened moths in the glare of car’s lights, seen from the back seat. And these images arrived with a quiet, but palpable sense of shock, as I realised how long it’s been since I’ve anything like that here in England. Changes too big, too continuous, to be easily noticed.

One of the participants, an artist and botanist, offered a good word for making a space for grief, that’s stayed with me. Welling: a word to welcome, and to un-fuss, the arrival of tears. She spoke, through tears, of a surprise encounter with a specimen of a thought-to-be-extinct flower: the welling that came at the realisation that this small flower was among the very last of its kind. And from Margeretha, we learnt another word for what grief asks of us, one that spoke more directly to my experience than anything else said that night: reckoning.

We’d spoken of Steven Jenkinson, Griefwalker, who teaches his students to honour grief as the form of praise that it is. The depth of any sadness, a measure of value for the mourned-over. I immediately liked this idea of sorrow-as-praise, just as I appreciate welling as a good word to affirm levels of experience that all our ‘eco-critical discourse’, however subtle, is surely helpless if it excludes. But this reckoning struck a more personal chord for me. Truth be told, around what’s alluded to by these bleak, proliferating phrases – declining baselines, 6th mass extinction, the great narrowing, abrupt global warming – welling is not a thing that easily visits me. Perhaps my emotional literacy does not reach that far, or that deep. Grief is out there, for sure, but for me anyway, it lives somewhere more obscure, more remote than tears. Even on the occasions of personal grieving that I’ve encountered, its as if tears have had to cross some great distance to reach me, arriving from a far remove to which they have then promptly withdrawn. A welling, yes, but one with a long tidal reach. And around these greater currents of loss, grief is more often known, I think, as a thing inferred by its absence. A numbness, or perhaps a muteness. One that carries with it an obscure sense of pressure - of being somehow unable to voice, or even to speak of, what’s there.

Reckoning: a word that takes me straight to this familiar territory. To a numbness that exists more in the body than the head, and is felt as a kind of drawing-down, drawing-in. And I see that for me, this place of reckoning has everything to do with art, with what I come to both art and poetry looking for. It’s a word, too, with which to weigh the difference between thinking a thing, even a thing known only by its absence, and touching that thing, tasting it.

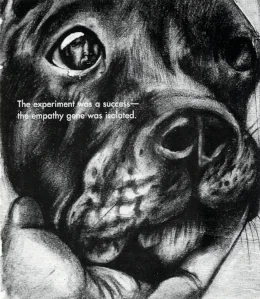

What do we ask of art, before the implacable escalation of anthropogenic mass-extinction? Often, the talk seems to be of inspiring, of motivating, emoting. Of awareness raising: image-making as a constructive contribution to the fight, a subtle and effective tool in the great struggle to turn our culture around, ‘before its too late’. Art deployed as a sophisticated form of message-dissemination, one that just might – who knows – finally stir us from this weird, collective inertia.

I’ve long found myself curiously unable to engage with any such sense of mission. Facetiously, but without irony, I’d say that art has more important work to be doing than saving the planet. First and foremost, I’d say that what I look to art for is soul-retrieval. The recovery of lost soul. And for me, art’s ability embody this process of reckoning is really the heart of the matter, now more than ever, as we stare dumbly at what we’ve become, alternately wringing our hands, blanking out, caught up in eco-busyness’ fidgety displacement activity before the mind-numbing scale of what our own collective existence presents us with.

If I look to my own work to make a contribution to our understanding of ecological recovery, to map a process of cultural recuperation, to articulate a working model of spiritual ecology, I notice something both curious, and unmistakable. Without fail, the work cringes in embarrassment, and rapidly peters out. As if all such rhetoric took hold the stick by the wrong end, and in doing so, placed an impossible weight of expectation on these uncertain, meandering threads of thought. But if, instead, I turn to drawing and to writing for this more immediately personal reckoning, I find a process unfurling of itself - already underway, with or without my conscious involvement, or intent. There’s a kind of welling present within that unfurling, yes, but one that moves independently, within the body of the work, and has strangely little to do with any cathartic outpouring of emotion.

I’m grateful to have taken away a word for this process from the Coastal Reading Group’s ceremony. And grateful, too, for those three good hours of unhurried conversation under the patter of summer rain on canvas, during which we bound our grief into the earth, wove its stories into wool and clay, held their weight in our hands, then set them down.