A reflection on the 2014 R.A.N.E. Soil Cultures Forum, published as an editorial in Soil Culture, Cornerhouse 2015

'Our need for an ecology movement, animal rights advocacy, and a world wildlife fund begins in our dreams.'

James Hillman, Dream Animals, Chronicle Books 1997

One year on, I’m still mulling over the many impressions left by last summer’s Soil Cultures Forum. An image that has kept recurring, both during the forum itself and within that year-long cud-chewing, is that of mycelium: both as an ecological entity, and as a metaphor that might prove useful for steering arts practice. What follow here are notes that I took during three Soil Cultures Forum talks, followed by some of the questions that each talk provoked. With regard to the notes, I’m not always sure, now, which parts of the material are mine, and which the speakers’. On the whole it’s the latter, but both my selections and my comments reflect an unapologetically personal bias, that will, I think, speak for itself.

Richard Kerridge

Around eco-criticism lurks the idea of the poem that will save the world: the artwork that will change us, that will bring about a shift in perception, one which will in turn enable us to change our behaviour. Has art, poetry, literature ever achieved this? Perhaps very rarely, possibly not at all. The general case is rather that our work is borne along by cultural trend, but in going with that current it forms a small part of it, one that contributes to it’s strength, momentum. The heroic notion of the artwork as a driver of cultural change is both a distraction, and an insupportable inflation, one that places a weight of expectation on creative practice that it can never live up to. We need to set aside the notion of the artwork as monumental icon of the paradigm-shift we seek, and look instead to creative practice as a quiet turning of the soil: to the artwork, poem and story as micro-organism, as connective mycelium - the manure that feeds and renews the myriad invisible life of that soil.

What might we make of mycelium, of micro-organism, of turning the soil, as metaphors for arts practice, and for communities of practice? Culture imagined as a subsoil fungal web: a connective matrix that sustains communities of organisms - forests, people - through a process of reciprocal nourishment. An example from biology: solitary redwood saplings grown in light conditions equivalent to the interior of a forest will invariably die (Derrick Jensen, Dreams, 7 Stories Press 2011). They survive to adulthood within the forest, only because fungal mycelium conducts nutrients from the surrounding mature trees to the young, until they are able to reach the light themselves. Ecosystems: a dry word for living communities. Their core principle: reciprocity, vs. the tired old fantasy so beloved of end-stage capitalism, ‘nature red in tooth and claw’.

Stefan Harding

We’ve tried an environmentalism based on information. Strangely, that didn’t work. We thought if we gave people the information about what was happening, they’d be changed. But no, they weren’t. Then we tried fear, but that didn’t work either. Frightening people doesn’t change their behaviour. What’s left? The only way that we can address these problems is through love. We have to re-learn, as a culture, to love the earth. Nothing else will do. We have to learn what it means to love the earth, because it is only if we love the earth that we will not be willing to see it destroyed.

So far, so Schumacher College. Great. But if we agree with, and celebrate every word of that – I do - what of it? What are the practical implications of that, for arts practice? Deep Green Resistance, for instance, have framed a campaign of disruptive sabotage, one who’s stated intention is to ‘bring down civilization’, in exactly these terms. Their version of that question: How does love behave, faced with the accelerating destruction of the loved, by one’s ambient culture? On a quiet summer day in Falmouth, that sounds like melodrama. But is it? I meet many at gatherings such as this who reject DGR’s solution, but far fewer who question their diagnosis of the problem. If we’re not making art in that militant spirit, then what, exactly, are we proposing? What manner of healing do art, poetry and storytelling have to offer, as we stand facing an accelerating anthropogenic mass-extinction, besides green message-dissemination and ‘awareness raising’? For those of us who find ourselves persuaded that what DGR et al say about the current trajectory of our culture is broadly true, how else might art and poetry respond to that, if not as a call-to-arms? And why?

Sam Bower

Sam begins his talk with two images. The first: an aged sepia photo of a Haida village, which includes a cluster of totem poles, standing at the village edge. The second: a single totem pole, standing alone inside the British Museum.

Our culture venerates the art object, but what is art, as de-contextualized object? The British Museum pole stands as the empty husk of absent stories that once infused and sustained a living culture of inhabitation. To the people who lived with the pole within its original context, the faces it bears were known to them by name, as part of their shared history. Those same beings, stories might appear in a tattoo, on the side of a boat, within a song sung whilst working, festival, taboo. Outside the museum at the heart of this dying culture of occupation, those faces have fallen silent – they tell only of absence. What we need is a renewal of cultural expression, rather than a renewal of artistic expression: to see that the artwork – of whatever kind – is only the visible shoot emerging from the living soil of culture. Renewing that soil is our real challenge, one that doesn’t necessarily require vast amounts of money. As with environmentalism, in our search for cultural adaptation we look in vain to charismatic mega-fauna within the arts, when in fact it’s the underlying soil that we need to attend to, to nourishing that connective culture of relationships, shared stories, communities.

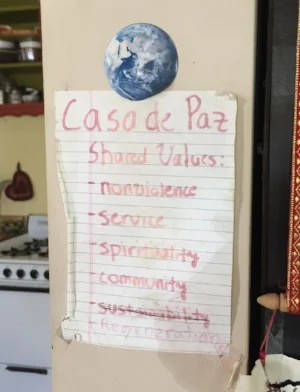

Mycelium, again. Or at least, it seems near at hand. Sam shows us a Vimeo film: the Casa de Paz project in Oakland CA, where he lives. An extraordinary experiment in socially-engaged, spiritually-attuned, communal living. A project based on something Sam refers to as Giftivism: the unfathomable power of acts of gratuitous generosity to change the world. Within the house’s kitchen, we glimpse a pinned-up list of five principles, that steer this experiment in choosing a better way to live. The last principle,‘Sustainability', has been crossed out and replaced with the word 'Regeneration’.

I like that. Perhaps regeneration is a good word for what art might have to offer, in the face of the radical unsustainability of the systems of living that we currently inhabit? I like it both for its inclusivity, and for its unconditionality. A work that all of us micro-organisms can, and do feed: art practice as a call-to-arms, a dream, a prayer, a thought experiment; as a slow turning of the soil that we can all lend our hands to, at any time. No ‘too late’, here.